Five debates occur!

Plato vs Foucault

Wittgenstein vs Rawls

Russell vs Aquinas

de Beauvoir vs Friedrich Nietzsche

Gould vs. Socrates

Round 1: Plato vs. Foucault

Setting: A timeless agora, where philosophers from all eras can convene.

Moderator: Welcome, esteemed thinkers. Today, we witness a clash of titans: Plato, the Athenian philosopher of Forms, and Michel Foucault, the modern analyst of power and discourse. The topic: the nature of truth, knowledge, and their relationship to power.

Plato: (Stroking his beard) It is an honor to engage in discourse with a thinker from so distant a future. I believe true knowledge resides not in the fleeting world of senses, but in the realm of Forms – perfect, eternal archetypes of which our perceived reality is but a shadow. Truth, therefore, is objective, discoverable through reason and dialectic, leading us towards the Form of the Good, the ultimate source of all being and knowledge. Justice, beauty, virtue – these are reflections of those perfect Forms, attainable by those who strive for wisdom. Imagine a perfect circle, existing not drawn on any surface, but as an idea, a blueprint for all circles. That, for me, is the nature of true knowledge.

Foucault: (Adjusting his spectacles) Respectfully, Plato, your notion of a transcendent realm of Forms strikes me as a dangerous fiction. You posit a universal truth existing outside human experience, yet I argue truth is not a pre-existing entity waiting to be discovered, but a product of power relations. Discourses, the systems of thought and language that shape our understanding, are not neutral conveyors of truth but instruments of power. They define what is considered “true” or “false,” “normal” or “deviant,” and thereby regulate and control individuals and populations. Your perfect circle, Plato, is only perfect because we’ve agreed, through shared language and mathematical systems, what constitutes perfection. That agreement itself is a product of historical forces.

Plato: But surely, Foucault, you cannot deny objective reality! The laws of mathematics, the principles of logic – these are not mere social constructs. The Form of the Triangle exists independently. It is this Form that allows us to recognize and understand triangles. Similarly, the Form of Justice provides the standard by which we judge actions and societies. If there is no objective justice, then is any act justifiable?

Foucault: I do not deny a material world, Plato. However, our access to it is always mediated by discourse. Even your “mathematics” and “logic” are expressed and understood within specific linguistic and historical contexts. They are tools developed and deployed within power structures. Consider the very concept of “reason” itself. Who defines what is reasonable? Who benefits from that definition? What is deemed unreasonable is often silenced, marginalized, even pathologized. This is not about objective truth, but about the power to define truth.

Plato: You speak of control, Foucault, but I speak of liberation! By grasping the Forms, we liberate ourselves from ignorance and the tyranny of the senses. The philosopher, through reason and contemplation, ascends to true knowledge, guiding society towards justice and harmony. My ideal Republic is governed by philosopher-kings, those who have glimpsed the Form of the Good.

Foucault: Your philosopher-kings, Plato, are the epitome of what I call “pastoral power.” They claim superior knowledge to justify their control, shaping souls and dictating lives for their own “good.” This power, originating in religious institutions and permeating the state, operates through individualization and normalization. It defines “normal” behavior and subjects individuals to surveillance to conform them. This is not liberation, but a subtle domination. You offer not freedom of thought, but adherence to a pre-ordained truth.

Plato: But without a fixed standard of truth and goodness, Foucault, how can we distinguish right from wrong? Are we not left with a relativistic world where all actions are equally valid? Is there no inherent value in striving for what is good?

Foucault: I do not advocate for moral relativism. Rather, we must constantly interrogate the power relations that produce our notions of morality and truth. We must be wary of any claim to absolute knowledge and focus on the specific contexts in which discourses operate. By analyzing power’s mechanisms, we resist its oppressive effects and create spaces for greater freedom and autonomy. Perhaps, instead of searching for a universal Good, we should focus on the specific harms inflicted by power and strive to minimize them.

Moderator: Time is drawing to a close. Any final thoughts?

Plato: I maintain true knowledge and justice are attainable through reason and the pursuit of the Forms. To deny objective truth is to condemn humanity to chaos. If everything is relative, then nothing truly matters.

Foucault: I argue truth is inextricably linked to power. By understanding how power operates through discourse, we challenge its dominance and create a more just world. It is not about finding the Truth, but about constantly questioning the truths we are given.

Moderator: Thank you, Plato and Foucault. Your contrasting perspectives offer invaluable insights into the complex relationship between truth, knowledge, and power, a debate that continues to resonate powerfully.

Round 2: Wittgenstein vs. Rawls

Moderator: Welcome to this evening’s intellectual showdown. In one corner, we have Ludwig Wittgenstein, the enigmatic linguistic surgeon. In the other, John Rawls, the architect of justice. The question before us: What is the purpose of philosophy? Let the battle of wits begin!

Wittgenstein: (With a smirk, cigarette in hand) Philosophy’s purpose? A better question might be, where does philosophy end? It is not a ladder to climb but a mirror to hold. My Tractatus sets the boundary—what can be said clearly must be said, the rest is silence. Ethics, metaphysics—they’re outside the realm of meaningful discourse. Philosophy clarifies, it doesn’t prescribe.

Rawls: (Adjusting his glasses, voice measured but firm) Wittgenstein, your linguistic acrobatics might impress in the ivory tower, but they falter in the streets. While you scrutinize the grammar of our thoughts, injustice flourishes unchecked. My Theory of Justice is a call to action. Imagine, if you will, a society constructed from behind a veil of ignorance. No one knows their place; thus, fairness is enshrined. Can language games offer such a vision?

Wittgenstein: (Eyes narrowing, leaning in) Ah, the veil of ignorance—a clever trick. But isn’t it just another word game? You talk of fairness as though it’s a universal constant, yet it shifts with context, with culture. Your thought experiment abstracts from reality, constructing an ideal that dissolves upon contact with the messy, multifaceted lives people actually lead. Justice, as you speak of it, is just another phantom of our linguistic habits.

Rawls: (A slight smile playing on his lips) You accuse me of abstraction, yet you retreat into the minutiae of language, evading the real. People are not abstractions, Wittgenstein. They bleed, they hunger, they suffer under systems of inequality. The original position is not a game, but a tool for thinking about justice without prejudice. It’s a method to ensure fairness transcends personal biases.

Wittgenstein: (Pacing, voice rising) And what of the chaos of human life, Rawls? Can your sterile procedural justice account for the lived realities of language? You assume fairness is a static concept, but it’s negotiated daily, in courts, in homes, on the streets. Look at history—grand theories promising utopia often lead to tyranny. Your framework is no exception. It’s a map that doesn’t fit the terrain.

Rawls: (Leaning forward, tone sharpening) History is replete with injustice because of the absence of fair principles, not their presence. The cries of the oppressed aren’t language games, they’re calls for justice. Without a framework, without principles, we drift into arbitrariness. Are you suggesting we dismiss these cries because they’re expressed through language? That’s nihilism, Wittgenstein, not philosophy.

Wittgenstein: (Challenging, eyes locked) You speak of cries as if they form a single chorus. But justice is many voices, many uses of language. You impose a monolithic structure onto something inherently pluralistic. Your veil of ignorance assumes we can strip away identity, but identity is the very fabric of human experience. Can you truly say your theory captures that complexity?

Rawls: (Calm but forceful) Identity is vital, yes, but it should not dictate the principles of justice. The original position safeguards against privileging one identity over another. It doesn’t erase identity but ensures fairness irrespective of it. Without such safeguards, justice becomes a weapon of the powerful against the powerless. Can you deny that philosophy has a duty to prevent this?

Wittgenstein: (Pauses, then with quiet intensity) Philosophy’s duty is to show the fly the way out of the bottle, not to build another bottle. Your framework risks becoming another trap, a system that claims universality but silences dissent by its very structure. Philosophy must stay grounded in the fluidity of life, in the way language is woven through our daily interactions.

Rawls: (Unyielding) And yet, without principles, that fluidity becomes a flood, washing away the weak. My framework offers a raft, a way to navigate the currents of society fairly. It’s not perfection, but it’s a start. Philosophy must guide us, not merely describe the chaos.

Moderator: (Stepping in, a bead of sweat on his brow) Gentlemen, thank you for this riveting exchange. It seems we stand at a crossroads between Wittgenstein’s linguistic clarity and Rawls’s moral framework. Both perspectives offer profound insights—and daunting challenges. Let us, the audience, wrestle with these ideas and consider how they might shape our understanding of philosophy’s role in the world.

Round 3: Russell vs. Aquinas

Setting: A grand library, filled with ancient tomes and modern texts, a fitting battleground for minds.

Moderator: Welcome, esteemed thinkers. Tonight, we witness a clash across centuries: Bertrand Russell, the champion of logic and reason, and Thomas Aquinas, the architect of Christian scholasticism. The topic: the existence of God and the role of reason and faith.

Russell: (Adjusting his spectacles, a mischievous glint in his eye) It’s a pleasure, though perhaps a futile one, to engage with a mind so thoroughly entrenched in the medieval miasma. Aquinas, your attempts to reconcile faith with Aristotelian logic are, to put it mildly, a magnificent failure. You present five ways to prove God’s existence, each riddled with logical fallacies. The cosmological argument, for instance, commits the fallacy of composition – just because every event has a cause doesn’t mean the universe as a whole must have one. It’s like saying because every brick in a building was carried there, the building itself must have been carried there. Utter nonsense!

Aquinas: (Calmly, with a gentle smile) My dear Russell, your modern sensibilities seem to blind you to the elegance of divine truth. My Five Ways are not mere logical exercises, but rather reasoned pathways to understanding the very nature of existence. The cosmological argument points to a First Cause, an Unmoved Mover, necessary to explain the contingent nature of the world we observe. You speak of the fallacy of composition, but you misunderstand the nature of God. He is not simply the sum of all causes, but the very ground of being itself.

Russell: (Scoffs) “Ground of being”? Such vague and meaningless jargon! You invoke this mysterious entity to plug the gaps in your logic. It’s a classic example of the god-of-the-gaps fallacy. We don’t understand how the universe began, therefore, God did it. But science is constantly expanding our understanding. We’ve made incredible progress in cosmology, in explaining the origins of the universe without resorting to supernatural explanations. Think of the expanding universe, the evidence for a hot, dense early state.

Aquinas: (Raises a hand patiently) Science describes how things happen, Russell, but it cannot explain why there is something rather than nothing. The expansion itself begs the question: what is the nature of spacetime that allows such expansion? Science operates within the realm of the contingent, the observable. My arguments point to the necessary, the transcendent. The very existence of contingency requires a necessary being.

Russell: (Leaning forward, his voice sharper) “Necessary being”? You’re simply playing with words! You define God as that which cannot not exist, and then claim this proves his existence. It’s a circular argument! It’s like defining a unicorn as a horse with a horn on its head, and then claiming that this definition proves unicorns exist. It’s a linguistic trick, not a proof. And what of the problem of evil, Aquinas? If God is all-powerful and all-good, why does suffering exist? Why do innocent children die of disease? Why is there so much pain and misery in the world? Consider the Black Death, Aquinas. A plague that decimated Europe. Was that God’s will?

Aquinas: (His expression turning somber) The problem of evil is indeed a profound mystery, Russell. But it does not disprove God’s existence. Free will, a gift from God, allows for the possibility of evil. God permits evil to exist so that greater goods, such as love and compassion, can emerge. Suffering can be a test of faith, a path to spiritual growth.

Russell: (Explodes with exasperation) Free will? A convenient excuse! You blame humanity for the suffering that your omnipotent God allows to happen. It’s a monstrous doctrine! And what of natural disasters? Are earthquakes and tsunamis also the result of human free will? It’s absurd! The world is full of gratuitous suffering, suffering that serves no purpose, that leads to no greater good. To claim that this is compatible with an all-loving God is an insult to human intelligence. Think of the countless animals that suffer and die in the wild, Aquinas. Where is the free will there?

Aquinas: (His voice firm, but tinged with sadness) God’s ways are not our ways, Russell. We cannot fully comprehend the divine plan. Faith requires trust, even in the face of suffering. The natural order can bring about destruction, but it also reveals the majesty of God’s creation. The world is a testing ground, a preparation for eternal life.

Russell: (With a dismissive wave of his hand) “Eternal life”? Another comforting myth! There’s no evidence for it, only wishful thinking. We live, we die, and that’s the end. To base your entire worldview on such unfounded beliefs is a profound intellectual failure. Think of the scientific method Aquinas. The process of observation, hypothesis, and testing. This is how we gain reliable knowledge about the world, not through faith.

Aquinas: (Staring intently at Russell) But reason without faith can lead to destruction, Russell. Knowledge without wisdom is a dangerous thing. Science can build bombs, but it cannot tell us whether or not to use them. It is faith, grounded in love and compassion, that provides the moral compass we need to navigate the complexities of the world. Think of the two world wars Russell. The immense suffering caused by technological advancement used for destructive purposes. Is this the sole result of reason?

Moderator: (Intervening, sensing the rising tension) Gentlemen, this has been a truly remarkable exchange. We’ve witnessed a clash of fundamental worldviews, a battle between reason and faith, between the temporal and the eternal. While you remain deeply divided, your debate has illuminated the enduring questions that have plagued humanity for centuries. It is clear that the tension between reason and faith will continue to shape our understanding of the world for generations to come.

Round 4: de Beauvoir vs. Nietzsche

Moderator: Tonight, we have a clash of titanic minds. Simone de Beauvoir, existentialist and feminist trailblazer, and Friedrich Nietzsche, the provocateur of power and prophet of the Übermensch. Our question: What is the essence of human freedom and identity?

Nietzsche: (With a sly grin, leaning back) Ah, freedom. It’s the plaything of those who refuse to face the abyss. True freedom, de Beauvoir, is the will to power—the courage to create one’s own values in a godless, indifferent world. The Übermensch rises above the herd, casting off the shackles of conventional morality.

De Beauvoir: (Eyes narrowing, leaning forward) And yet, Nietzsche, your Übermensch seems conveniently blind to half of humanity. Women, under your “will to power,” are often the means, not the ends. In The Second Sex, I unmask how society constructs women as the Other, subordinating them to men’s self-affirming will. Your philosophy, whether intended or not, reinforces this hierarchy.

Nietzsche: (Chuckling, a glint in his eye) The Other, you say? The weak always frame themselves as victims. Women, like all who crave power, must seize it. The Übermensch does not whine about being the Other; he transcends, creating his own identity. If women are the Other, it is because they have not yet willed themselves into being.

De Beauvoir: (Voice cold, cutting) Transcendence is precisely what I argue for, Nietzsche. But unlike your Übermensch, I do not abandon solidarity in the process. Women’s liberation isn’t about mimicking the tyrannical individualism of your hero but dismantling the structures that define them as less-than. Your will to power is, for women, a struggle against centuries of objectification.

Nietzsche: (Smiling, a hint of derision) Objectification? Such a modern complaint. Struggle is the essence of life, de Beauvoir. Power is not given—it is taken. Those who lament their lot in life have already forfeited their will. Your call for dismantling structures sounds dangerously close to the Christian morality I despise—resentment masked as virtue.

De Beauvoir: (Eyes flashing) And your philosophy dangerously mirrors the oppressors who justify domination with talk of natural order. You cloak yourself in the language of strength, but it’s just a veneer for old hierarchies. The struggle I speak of is not against life but against the artificial barriers imposed by patriarchal society. Your Übermensch ignores the collective dimension of liberation.

Nietzsche: (Leaned in, voice mocking) Collective liberation? There is no collective in greatness. The individual who rises above, who embraces his will to power, does not beg for society’s approval. The herd seeks equality; the Übermensch seeks excellence. If women wish to be free, they must cease pleading for fairness and assert their will—without apology, without dependence on others’ definitions.

De Beauvoir: (Coolly, with a measured tone) And yet, Nietzsche, even your Übermensch is bound by his context. You speak of creating values, but without acknowledging how power has historically been distributed, you reduce freedom to a privilege of the few. My existentialism reveals how we all navigate a web of facticity. Women must navigate not just their individual will but the systemic constraints placed upon them. Freedom, for women, is not just self-creation but collective redefinition of what it means to be human.

Nietzsche: (Eyes narrowing, voice sharper) Ah, the collective again. You wish to dilute the wine of greatness with the water of the masses. True strength lies in embracing one’s own path, unencumbered by the chains of collective morality. Your feminism, for all its defiance, remains rooted in the same slave morality I have long condemned.

De Beauvoir: (Raising an eyebrow, smiling faintly) And your Übermensch remains a fantasy detached from the reality of human interdependence. Even the strongest must grapple with others. The freedom I advocate is not weakness but a reclamation of subjectivity for those who have been denied it. If your Übermensch dismisses half of humanity’s struggle, he is not a god but a deluded tyrant.

Nietzsche: (Leaning back, smirking) Then let them rise, de Beauvoir. Let women prove their strength not through complaints but through action. Power respects power, not petitions. If women wish to overcome, they must do so with the same ruthless creativity as the Übermensch—without excuses, without appeals to fairness.

De Beauvoir: (With a steely gaze) Women’s freedom will not mimic the brutality of your Übermensch, Nietzsche. It will be a freedom born of solidarity and shared humanity. We do not seek to dominate, but to dismantle domination itself. Your will to power overlooks the most radical act of all—creating a world where no one is Other.

Moderator: (Clearing his throat) Thank you, both, for this electrifying exchange. We leave with much to ponder about freedom, power, and identity. Your passionate and piercing arguments remind us that philosophy is, indeed, a battlefield of ideas.

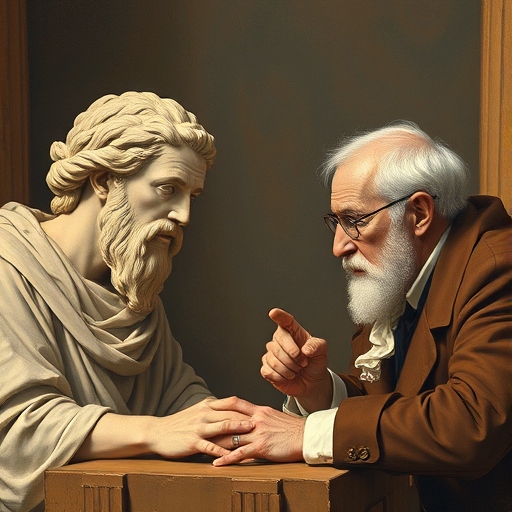

Gould vs. Socrates

Setting: The heart of a bustling Athenian agora, subtly reimagined with comfortable chairs and a modern, sleek podium. The sound of a distant marketplace hums in the background, but today, the square is dedicated to philosophy.

Moderator: Welcome to a most unusual intellectual exchange. Tonight, we have two figures from entirely different epochs—Socrates, the father of Western philosophy and master of dialogue, and Stephen Jay Gould, the eminent evolutionary biologist who bridged science and the humanities. Our topic tonight: What is the nature of knowledge, truth, and human understanding?

Socrates: (Looking around curiously, the faintest smile) This gathering is… curious. I usually find myself in the agora, surrounded by the many voices of Athenian men. But now, a different kind of audience. Tell me, friend Gould, you study the natural world, correct? What, in your eyes, is the ultimate goal of this study? What do you hope to discover, to know?

Gould: (Leaning forward, a warm smile) Indeed, Socrates, it is an honor. My work is centered on understanding life’s vast history—the processes that have shaped the myriad forms of life we see around us. We seek to understand the mechanisms of evolution, the patterns of change that unfold over immense stretches of time. It’s about making sense of the complexity of life through observable evidence.

Socrates: (Nods slowly) A history of life, yes. And yet, what kind of history is this? You speak of “change,” but what drives it? Is there some final cause, some telos toward which all this change moves? Is there a perfect Form of an organism, a perfect man, as Plato would argue? Does evolution have some grand endpoint or direction, or is it just… flux?

Gould: (Shaking his head gently, a hint of amusement) No, Socrates. Evolution is not a ladder of progress, nor does it strive toward any predetermined goal. It is more like a sprawling bush, with branches shaped by unpredictable events, contingent forces, and historical accidents. Adaptation is not linear, nor is it toward “better” or “higher” ends. The extinction of the dinosaurs, for instance, was a result of a random asteroid impact. Were they “progressing” before that? Hardly. Evolution is not about striving upward; it’s about surviving and adapting.

Socrates: (Pauses thoughtfully, stroking his beard) But if there is no ultimate goal—no end toward which the organism is directed—how do you know what it means to be a “dog,” for example? I understand that a dog may change in size or temperament, but in its essence, there is something enduring, something constant in its “dog-ness.” Does this “essence” not point to something more profound than mere chance?

Gould: (Firmly) The “dog” you speak of is a fluid, evolving concept. There’s no fixed, eternal essence of “dog-ness,” no blueprint beyond the genetic code. What we call “dog” is a collection of evolving traits, influenced by both natural selection and human intervention. Even the dogs bred for particular purposes by humans show the flexibility of nature. Your ideal “dog-ness” is a human construct, a tool to categorize. Evolution is about descent with modification, not chasing after eternal Forms.

Socrates: (Eyes narrowing, a touch more intense) But if there are no eternal forms, no universal truths—how can we know anything truly? How can we trust our knowledge if everything is in flux? If even a “dog” is a matter of shifting definitions, how can we hope to know the nature of abstract concepts like justice, virtue, or beauty?

Gould: (Pauses, considering) Knowledge, Socrates, is not a quest for final certainty. It’s a continuous process, one of observation, testing, and refinement. We don’t seek eternal, unchangeable truths. We seek the best possible understanding of the world based on evidence. Science doesn’t offer absolute truths; it offers robust, empirical models that explain the patterns we observe. It’s an iterative process, grounded in data, not ideals.

Socrates: (Leaning forward, piercing) But if knowledge is provisional—always subject to change—what then is the worth of it? If we cannot grasp unchanging truths, are we not forever condemned to be deceived by the fluctuating appearances of the world? If our knowledge of the cosmos is limited to what can be seen or measured, how do we know we are not missing something deeper, something beyond the senses?

Gould: (Visibly unsettled) Science is aware of its limits, Socrates. We make use of the best tools at our disposal, and even when those tools change, they bring us closer to a better understanding of the universe. The goal is not finality, but accuracy—what can be known within the constraints of our faculties.

Socrates: (Pushing) And yet, Gould, your tools are limited by the very faculties they depend upon. Are we not just interpreting through lenses that have their own biases, their own flaws? Even your scientific instruments are subject to human error, to the limitations of perception. Without a higher standard, how can you know that your methods will yield any “truth” at all? Is it not possible that you, too, are building on sand, without foundation?

Gould: (Pauses, slightly defensive) Science corrects itself. It is a self-correcting process. Our mistakes lead us to better models, and over time, we improve our understanding.

Socrates: (With a cutting, yet gentle tone) But what is this “correction” based on, Gould? If there is no absolute measure, no universal standard, how can you be certain you’re moving in the right direction? What guides you? If truth is nothing more than a collection of provisional models, how do you distinguish between a better model and a delusion? Can you not see the circularity? If you cannot access some eternal truth, then are we not left adrift, chasing our own tails?

Gould: (After a long pause, more hesitant) We trust the process, Socrates. We trust the method. Through rigorous testing and peer review, science builds knowledge that, while never final, is always closer to the truth than we were before.

Socrates: (Leaning back, quietly triumphant) But my friend, is not your “trust” just another form of belief? If truth is not fixed, but merely “closer” or “more refined,” then what separates your understanding from that of the Sophists—those who claim, too, to offer wisdom, though it changes with every argument?

Moderator: (Stepping forward, sensing a shift in the room) This has been a deeply thought-provoking exchange. Socrates, with his unrelenting pursuit of truth, has cast doubt on the foundations of science and the quest for knowledge. While Gould has eloquently defended the scientific method, Socrates’ questioning raises profound concerns about the limits of human understanding and the very nature of truth. It seems the search for knowledge remains as complex and elusive as ever, a pursuit of both observation and introspection. Thank you, gentlemen, for this intellectually stimulating dialogue.

Leave a Reply